Access to Collaboration Site and Physics Results

Supersymmetry is an extension to the Standard Model that may explain the origin of dark matter and pave the way to a grand unified theory of nature. For each particle of the Standard Model, supersymmetry introduces an exotic new “super-partner,” which may be produced in proton-proton collisions. Searching for these particles is currently one of the top priorities of the LHC physics program. A discovery would transform our understanding of the building blocks of matter and the fundamental forces, leading to a paradigm shift in physics similar to when Einstein’s relativity superseded classical Newtonian physics in the early 20th century.

Supersymmetric particles (or “sparticles”) are grouped into two categories with different properties that depend on the strength of their interactions with protons. Strongly-interacting sparticles may be produced with large rates and lead to striking, energetic events in the detector. Weakly-interacting sparticles are produced at lower rates and lead to less striking signatures, making them more difficult to distinguish from Standard Model background processes.

Since the LHC collision energy was increased from 8 to 13 trillion electron volts (TeV) in Run 2 to enhance the discovery reach, a wide variety of searches for strongly-interacting sparticles have been performed. Null results in these searches indicate that if they exist, strongly-interacting sparticles must be very heavy – at least several hundred times heavier than the proton. Due to the smaller production rates, larger data samples are required to probe weakly-interacting sparticles, and more optimized selection criteria are required to tease apart the small signal from the background.

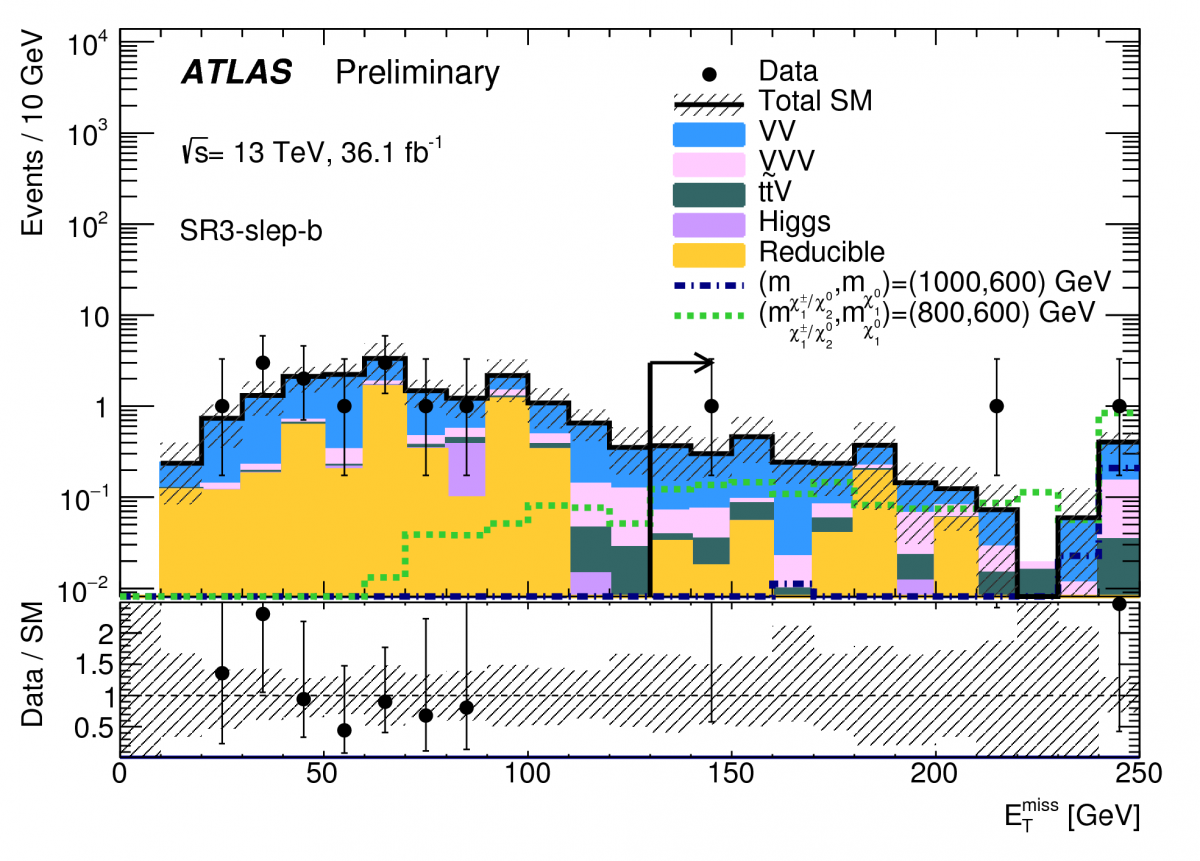

ATLAS physicists presented one of the first Run 2 searches for weakly-interacting sparticles at the LHCP 2017 conference. The search targets the production of sparticles called charginos, heavy neutralinos, and sleptons. If produced at the LHC, these particles would decay to leptons (electrons or their heavier cousins, the muons) and stable dark matter particles called light neutralinos. These dark matter neutralinos would carry away unseen energy since they do not interact with the detector, leading to unbalanced collision events that appear to violate momentum conservation. This “missing transverse momentum” is the key signature exploited by the ATLAS detector to infer the production of dark matter particles.

The analysis selected collision events containing two or three electrons and muons and large missing transverse momentum. The figure shows the measured distribution (data points) of missing transverse momentum in events with three leptons, compared to that expected from the Standard Model (coloured histogram). No significant deviation from the expectation was observed. The results were used to set stringent limits on weakly-interacting sparticles with masses as large as 1150 billion electron volts (GeV), the heaviest such particles yet probed at ATLAS.

Weakly-interacting sparticles may have eluded detection in this search if they are produced with very small rates or do not produce much energy in the detector. Both of these features are expected in models with light higgsinos, the super-partners of the Higgs boson. Future searches will exploit larger data samples to achieve sensitivity to even smaller production rates. Improvements to these searches are underway that employ reduced lepton momentum thresholds and novel signal vs. background discriminating variables to enhance the sensitivity to models that produce even less energy in the detector. A discovery in these searches could shed light on the nature of dark matter and help resolve the “hierarchy problem,” a fundamental theoretical shortcoming of the Standard Model leading to a predicted Higgs boson mass that is some 16 orders of magnitude too large.

Links:

- Search for electroweak production of supersymmetric particles in the two and three lepton final state at √s = 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector (ATLAS-CONF-2017-039)

- Presentation by Antonella De Santo: SUSY electroweak searches with ATLAS, and Till Eifert: Electroweak Supersymmetry

- See also the full lists of ATLAS Conference Notes and ATLAS Physics Papers